The expression “you’re glowing” is a common compliment used to indicate someone appears healthy, happy, or has some other positive physiological state—this saying frequently comes up when people notice signs of pregnancy. However, in actuality,

humans

(as do all other living organisms) genuinely emanate a luminescence primarily due to the organism’s metabolic and cellular activities.

This light emission, in technical terms, is produced by entities referred to as biophotons (or ultra-weak photons). Scientists

have been studying them for decades

, examining their variations attributable to aging, gender, health, and numerous additional factors. Currently, researchers at the University of Calgary have studied the emission patterns of these photons.

mice

Before and after death, illustrating how they rapidly fade following an organism’s demise. The findings from this research were published in

The Journal of Physical Chemistry Letters remains unchanged as it is the title of a scientific publication.

.

“The reality of ultraweak photon emission is now beyond dispute,” said Dan Oblak from the University of Calgary, who was the senior author of the study.

told

New Scientist

This truly indicates that this issue stems from more than just an imperfection or other biological processes. It is actually derived from everything.

living things

.”

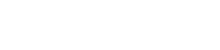

To document this procedure in real-time, Oblak and his team obtained two one-hour exposures utilizing sophisticated digital cameras designed for recording individual photons.

photons

Released by four mice, the study observed that prior to each session, both the living and deceased mice underwent a 30-minute adaptation period in darkness before being imaged. The findings clearly differentiate ultraweak photon emissions (UPEs) from live versus dead mice, indicating persistent emissions aligning with regions of elevated metabolism in the mouse preceding death.

Although live mice produce strong ultraweak photon emissions (UPE), suggesting active biological processes and cell activity, deceased mice display minimal UPE emission, leaving just a handful of ‘bright spots.’ These bright areas in dead mice correlate with even brighter regions found in their living counterparts, indicating the halt of metabolism and related activities.

energy

variation,”

the authors wrote

.

Certainly, these photon emissions are not unique to animals alone; thus, Oblak and his team employed a comparable method to examine UPEs in plants—a specific example being the umbrella tree.

Heptapleurum arboricola

They examined the release of biophotons resulting from plant damage, along with the use of specific applications.

chemicals

such as alcohol (isopropanol) and hydrogen peroxide (H

2

O

2

), and benzocaine. In these cases, the plant seemed to

increase

It refers to biophoton emissions, which might have significant applications in assessing the well-being of the globe’s woodlands.

“As the temperature rises, so does the intensity of UPE emitted by plants; essentially, increased temperatures lead to greater UPE emission […] Additionally, UPE can serve as an indicator of damage within plants, with damaged sections producing a larger number of photons,” they noted. “Studying the UPE emissions from Plants”

plants

It could serve as an easy approach for non-invasive tracking of health irregularities and plant development across various environmental settings, beneficial for both plant biology studies and farming techniques.”

As

New Scientist

Previous research has also observed the varying ” glowing” phenomenon in living organisms.

cells

Even specific bodily components have been studied for their biophoton emissions, but not whole animal organisms like in the current research. Enhancing these analysis techniques might enable researchers to utilize biophotons as a non-intrusive method for assessing human well-being and gauging whether one’s natural luminescence truly signifies good health.